Layers of meaning - the creation of our overtourism imagery

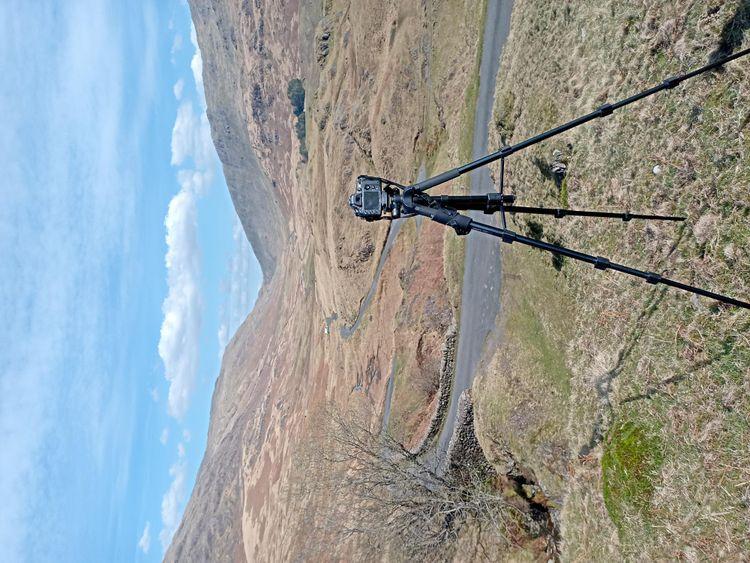

Natacha de Mahieu is a Belgian photographer and videographer, whose recent series of composite images set out to spark a conversation about overtourism. After she’d been out working in St Ives, The Lake District and Durdle Door for us, we chatted to her about the nature of her work, the reaction she’s had and the long hours of editing.

What made you get into this subject as an artist?

The idea came from my own experience as a tourist. I did a long trip, to Thailand with my bicycle. And it was quite a slow travel experience, but I crossed a lot of tourist hotspots. Between those hotspots, I had to cycle a big space in the country where there was nobody. The contrast between very nice places with no tourists and then another place that looked much the same but with a lot of tourists, was a bit absurd for me. You ask yourself, why are there a lot of people here and not like, metres away? It's the same landscape. But there is nobody? Nobody?

Why do you think that happens?

It's because of infrastructure and also, perhaps, security. But there’s an element of the way travel has changed across the world in the last decade or so and that’s down to social media.

Social media? How so?

So, I came back from the Thailand trip because of Coronavirus. And the only way I found to travel when I was home, was to stay on Instagram and look at pictures, travel pictures. And I was like, oh my god, it is always the same pictures in the same place. The same colours, the same compositions. It was very strange. I had a feeling that it was having an impact on the way I was looking at things, and it was quite disturbing because it's unconscious. As a photographer, your way of looking is quite important. You have to have your own way to look at things and it can change if you spend too much time on Instagram.

And that effect is changing how we travel?

Yeah I think so. Instagram is a big inspiration for young people to find holidays. They know that there will be a lot of people but they are attracted by the spaces. They go preciesly because it's so popular. And people have always taken photos, but now we don't have to only take a picture. We have to share it. That's the difference between now and 10 or 20 years ago. We have to share it and that changes how we experience it. We don't look at a landscape when we’re with our phone. We are just focused on the phone. But then everyone is making a frame with nobody in it and the contrast between what you can see on social media and the reality is so big. I was looking for a way to mirror that, but also to understand and to question it. So that's how I started the project.

How do you create the images?

I had an idea of doing time lapses and I thought at first that I would have to stay in one place for a whole day, perhaps even more, to get enough people to have a picture at the end that would show what I wanted to show. But for the one in The Lake District, I had everything I needed in one hour. St Ives, it was a full day, but it was very large scale and I had to think about the changing water level. Plus, I went before I started to choose the location to shoot from and when I went back the next day all the boats had moved and I was like, oh shit.

And then a lot of editing?

A LOT of editing. I think three weeks to one month for most of them, especially St Ives. First I select some images that I definitely want, where people are doing interesting things. Then I go through and maybe keep the same people in the image several times, or find others that I want to add. Then it’s lots and lots of work with shadows to balance the lighting!

Do you mean them to look like real photos?

No. I try to hold that ambiguity. Is it real or not? Maybe someone thinks it is, but if they look at the details, they can see it. It's fake. But it's interesting to make people question and understand. It's a bit like Instagram. Instagram is not reality. I try to stay as close as possible to the reality but I say all the time that it's not a single picture.

And do people... get it?

It starts a conversation. You've got people thinking why is done like that? You could do it in such a way where people trust the pictures immediately. People don't read them, they just trust them. But it's a construction, so that's not what I want. I want that they understand the project and process also.

So have you started that conversation now?

I think there was already a conversation, but when I saw how much reaction there was to the images, I think it's become even more. I had a lot of messages from people who didn't realise that there were so many people in these places and how geo localisation can have an impact, that kind of thing.

Have you been able to capture that impact?

I have tried to document it with my drone. But sometimes it’s visible and other times not. So I'm not convinced at the moment that what I made would have impact in a visual way like the current series does. I'm thinking about it, how to show it, but for now it’s enough to show the numbers of people and talk about the problems that arise.

Has the project changed the way you travel?

Well I’m a van lifer, but I’m not perfect, as a tourist. I did that project to question my own way of travelling too. So I'm also a tourist going to those kind of places. I'm quite lucky with my job to have time to travel and move in a slower way, by bicycle or in my campervan, but I try to just to be happy, be respectful of where I am.

What would you say to people who don't have that time?

What I discovered when I did this project in Europe is that Europe is a very nice continent! You don't have to go to Thailand or Chennai to find beautiful places. I think you can just go to France, to the UK to Spain. You don't have to go very far to find difference and exotic places. I think that's the most important thing, to find interesting places close by.