Is nature caffeine for creativity?

As of 2022, half of all human beings live in urban areas across the globe. In fact, in England, the figures are even more stark: 56.3 million (82.9% of England’s population), and it’s getting worse – the UN estimates by 2050, it will be 3 in 5 of us worldwide. Campaigner Ellen Miles tracks our slow deprivation of green spaces in her manifesto, Nature is a Human Right – a compendium of work from world leading scientists, activists, artists and more. Each of the authors speaks on the subject through a unique lens, from mental health to anti-racism, climate activism to disability, each outlining the positive effect immersion into nature has on our lives, in very tangible terms.

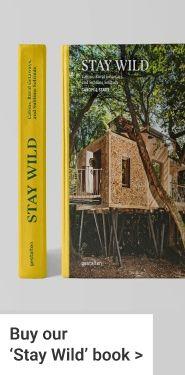

We're thrilled to share this exclusive extract from Daisy Kennedy's essay 'Is nature caffeine for creativity'. Nature is a Human Right is published by DK and available via Bookshop.

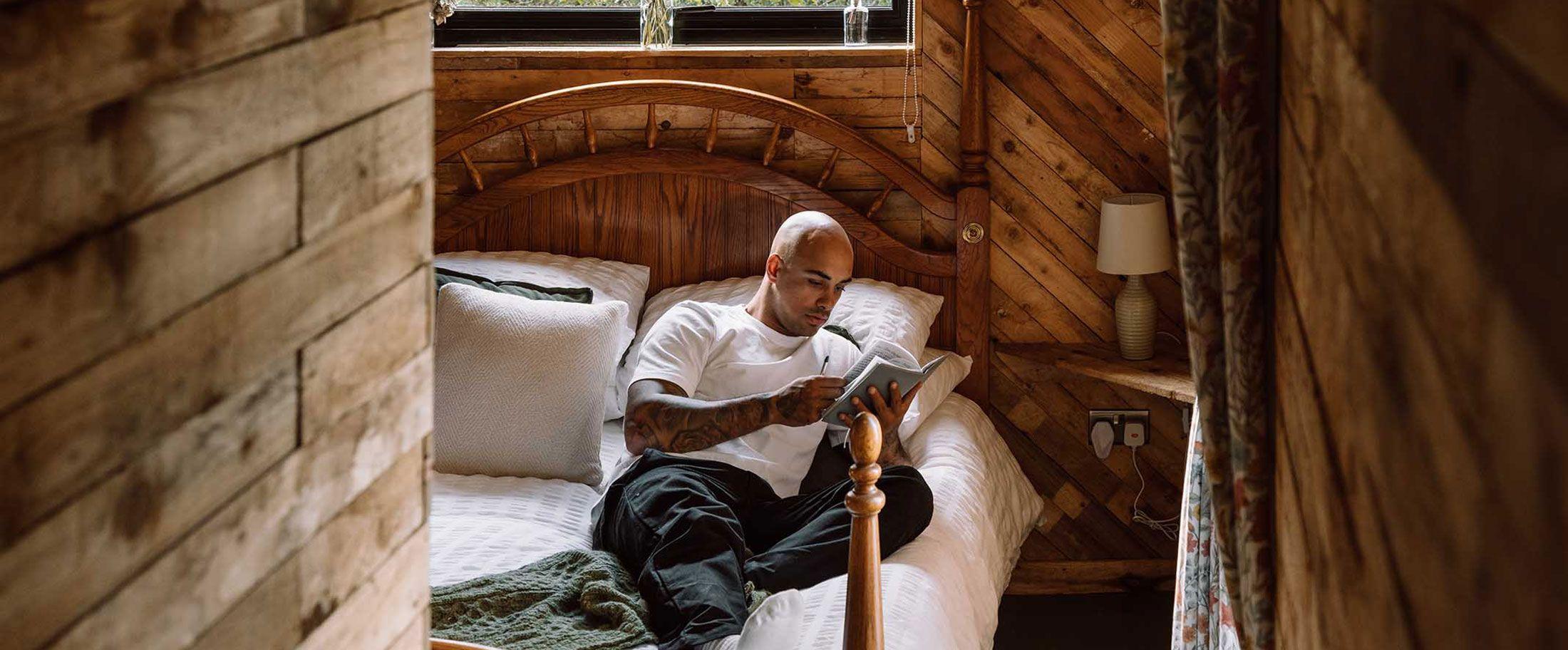

The relationship between nature and creativity has fascinated me since primary school. Tongue sticking out, crayon in a tight fist, viciously rubbing paper against a tree – I remember feeling like time was endless, like nature was my infinite playground.

This fascination extends far beyond me. Since the dawn of human history, creativity and nature have been linked. Of course they were; when Homo sapiens were painting on cave walls 45,000 years ago, there was little else to work with, content- and medium-wise (biro and paper were out of the question, let alone NFTs.) Since then, nature has continued to provide inspiration and refuge to poets, painters and pianists alike. So much so that Post-Impressionist Pierre Bonnard asserted, “Art will never be able to exist without nature.”

History is on his side. Wherever we look, we find nature inspired art. Ancient Roman cities were decorated with frescoes and mosaics of natural scenes: songbirds perching in bushes, colourful blossoms, fruit-laden trees. In 17th-century Japan, haiku brought drama to fleeting natural phenomena, while paintings and prints by the likes of Hokusai depicted trees, mountains and waves. In 19th-century Britain, the Romanticists wove descriptions of landscape with emotional undertones; William Wordsworth was a self-professed “worshipper of nature”.

Bonnard’s claim also has scientific backing: it seems that nature makes us (more) creative. The University of Kansas and the University of Utah conducted an experiment in which they gave participants three seemingly random words – for example, “cream”, “skate” and “water” – and asked them to find a fourth term that links them. In this case, it could be “ice”. After a few days immersed in nature – backpacking in Alaska, Colorado, Maine or Washington state – the “naive hikers” were 50 per cent better at coming up with the umbrella links. In another study, a German research team found that just a glimpse of green makes us more creative: participants were 20 per cent better at coming up with different uses for a common object when they’d seen the leafy colour beforehand.

What is this magic that nature works on our right-brained activity? To really investigate how nature and creativity are intertwined, we need to examine what rouses the creative mind.

Wild Beauty

Nature’s beauty is not only inspiring, it’s also good for us. Beauty chimes with our souls in a way that brings a sense of fulfilment, comfort and joy. And, as Richard Taylor’s research shows, we are built to find nature’s forms beautiful. Writer and activist Alice Walker famously said of our fondness for nature’s forms: “In nature, nothing is perfect and everything is perfect. Trees can be contorted, bent in weird ways, and they’re still beautiful.”

Data scientist Doctor Chanuki Illushka Seresinhe is an expert on how nature’s beauty benefits us. Through several studies, involving tens of thousands of participants, she’s discovered that beautiful places improve people’s health and happiness. Especially interesting, she says, was her finding that, if a scene is full of a variety of natural features (like trees or valley contours), it was considered more beautiful; if it was just flat grass, people rated it lower. “Just green wasn’t good enough,” she explains. “Not all green space is created equal. People will say, ‘OK, you have to put some green space in that neighbourhood’, but nobody considers how important it is to make that green space beautiful. Without this, people aren’t going to use it, or benefit from it, in the same way. Nature is important, but you can’t just slap some lawn down and go ‘that’s fine’. There’s something about wilder nature that people need, and are innately drawn to.”

Molly confirms this innate desire for wildness: “I was raised in North Yorkshire and, while the rolling Dales were beautiful, the rugged moorland always caught my eye more. My work is rooted in uneven and unpredictable textures, in mess, in roughness. I want to be as wild as those heathers and rocks.” Painter Tai Shan Schierenberg’s childhood also sowed the seeds for a relationship with the wild. Growing up on a farm, he says, has left him with “a strange relationship with nature: I understand that almost none of the landscape we enjoy is natural ... and that nature is pretty brutal.”

Nature’s beauty also elicits a sense of awe. Psychologists Stacker Keltner and Jonathan Haidt define “awe” as a feeling we get when confronted with something vast, that transcends our frame of reference, that we struggle to understand.Awe, and being awe-struck, can bring a host of benefits – including boosting creativity. Feeling awe makes time feel abundant, offering a creative haven for the mind to incubate ideas and wander freely. From ancient paintings of the vast night sky, to clickbait articles promising “10 Images of the Deep Sea that Will Shock You”, the overwhelming sense of awe is both a stimulus and springboard for creativity.

The authors

Ellen Miles is an environmental justice activist from London. She is the founder of Nature is a Human Right, the campaign to make access to green space a right for all, and Dream Green, a social enterprise that educates and equips people to become guerrilla gardeners. In her spare time, she is a guerrilla gardener, and runs a local action group in Hackney.

Daisy Kennedy is a writer and playwright from Wakefield, West Yorkshire, who now lives in Bristol. Since graduating from the University of the West of England with a degree in Drama and Creative Writing, she has had various plays produced with her theatre company Mismatch Theatre. Daisy was a finalist at the 2018 Wicked Young Writers Awards with her short story Tickets, she was awarded runner up in the Bristol Playwright Festival with her play Tic Tac Toes; and her most recent play, BLOOMERS was awarded first place in the 2020 Bristol One Act Festival. Daisy has been environmentally conscious since she was an eco-warrior in Year 6, she loves the outdoors and is passionate about creating work that advocates making green spaces accessible for everyone.