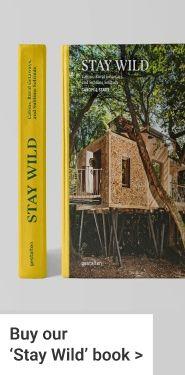

The meaning of (cabin) life, by Jack Boothby

We first interviewed photographer and cabin lover Jack Boothby in 2020 for our book, Stay Wild, where this essay first appeared. He talked about what cabin life meant to him and the experience that set him on a long road into the woods.

It’s hard to say where my love of cabins started, because until later in life I didn’t know it was even there. When it finally revealed itself to me, it brought a youth I’d almost forgotten flooding back. There was something in the freedom of the wilderness that not only reminded me what I’d loved about the outdoors as a child, but called to me even now as an adult. I realised that what nature offered me now was the same thing it always had. All I had to do was throw myself into it, just like I used to when I was a kid.

When we were young we went camping, like most families did, cooking on wobbly stoves, going on hikes and shouting at mum to put the camera down for once. I was a Scout as well, so I spent great weekends out in the woods building bridges, making slingshots, climbing trees. I barely noticed the places we stayed in. If you give a 10-year old the choice between appreciating a cabin’s rustic aesthetic and jumping into a muddy ditch, you know which one they’re going to choose.

As life got more complicated I found myself, as most of us do, spending less time in nature and less time doing things just for fun. On some level I knew I was missing something and I started to get drawn to beautiful outdoor imagery I’d see on social media. The memory of those days of freedom and simple joy started trickling back. With an adult eye, I could see how the cabin was at the heart of that lifestyle, how the structure and the setting could give us the space to be children again. I became obsessed with finding the places that would make that possible and tapping back into a time when I was happy almost because I never stopped to think whether I was happy or not.

My very first trip in search of that feeling was to Glencoe in Scotland, where I found a cabin surrounded by the trunks of looming pines. The silence, the sunlight and the sweet smell of damp earth were all instantly evocative. It felt incredible, but it was about to get even better. In the early hours of the morning I woke up to find a strange bright light filling the room. While I’d been sleeping, a foot of snow had fallen and the rising sun was shining off it. It felt like a mythical Christmas morning or those days when you woke up and knew there was a good chance school would be cancelled. I gave in to my inner child completely and ran outside to spend hours taking pictures of the pristine snow. There was that thick silence you get when every edge is softened, the snow was sparkling and I didn’t notice the cold. From that moment on I was hooked.

My childlike enjoyment of cabins would come as no surprise to the people who build them. They’re tapping in to the same feeling when they set out to create their incredible spaces. In the Kielder Dark Sky Reserve, in Northumberland, I visited a place that was described as having a folding roof so you could watch the stars. As I made my way there, I imagined something like a giant skylight, but I’ve never been happier to be wrong. Two whole sides of the triangular building lever gently back like a drawbridge and reveal the stunning clarity of the night sky. Any sensible adult who wanted to stargaze would just have put some good reclining chairs out on the deck, but this was the kind of thing a child would draw. It felt like a spaceship and I couldn’t believe someone had actually built it.

On another trip in Yorkshire, I celebrated my twenty-fifth birthday in a treehouse that had a slide down into a games room. Again, this was the sort of thing you’d have found stuck to my mum’s fridge with “Jack, age 10” scrawled on the bottom, but here I was arriving feet first at high speed into a room full of, let’s be honest, toys. On that trip I happened to be with a group of my oldest friends and I could see them responding the same way I was. We all regressed, in the best possible way, to our ten-year old selves as nature and a touch of creative magic blew away all the structure and worry that life slowly surrounds you in.

I’d noticed a similar effect no matter who I took with me on my cabin stays. Friends, family, even people I’d only just met. We talked more than we normally would but were also happier to spend time silent, enjoying our surroundings. There was an almost visible relaxation as we all connected with something either nostalgic or possibly even more primal, a sense of wildness that was deep and powerful. It was a feeling that had been the unseen background of my fondest moments as a child and I felt enormously grateful that it was now becoming a part of my favourite ones as an adult as well.

I’m not the first person to say there’s so much we can learn from children, but I totally believe it. What I try and do with my photography isn’t just to take beautiful images, but to capture that spirit of adventure so effortlessly reified by a kid in the woods. So many of us experience that so rarely these days and there are some who, for various reasons, never get out into the countryside at all. I want to reawaken the child in them and inspire them to explore that part of themselves further. My dream is to own a huge piece of land and build cabins that touch on every style, from the clean Scandinavian places to the old west frontier, so people could see how innate that desire for a simpler life is in all of us. That’s a long way off, so for now I’m doing what I can to tell the stories that cabin life inspires. I feel like it would be a much better world if we could all ditch some of our precious adult seriousness and rediscover the childlike joy of running wild.