A Life More Wild - Series 3 Episode 2

Nick Hayes

Nick Hayes on The Right to Roam, Silt Witches and getting arrested

In A Life More Wild we walk and talk in the countryside with fascinating people, transporting you to the great outdoors and helping you connect with nature through their unique perspectives. In this episode, we join Nick he explains the right to roam, silt witches and getting arrested.

So, we come down to the river and ironically, there was a sign saying, not 'No Trespassing' but 'access by permission only' and we are hilariously, quite unsure of whether or not we can walk there.

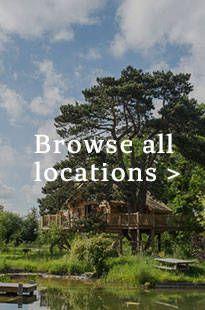

I'm Chris from Canopy & Stars, and this is A Life More Wild. When you're going to meet Nick Hayes, campaigner for the right to roam in England and author of The Book of Trespass, being held up by a sign on a fence is painfully ironic. Soon enough, Nick did wander over and cured us of our reluctance to cross that boundary. And that's a small version of what he's trying to do on a national scale. He's one of the most prominent voices of the campaign for The Right to Roam in England. He's also an illustrator and musician, who thinks that our broken relationship with nature is bound up with the loss of our cultural heritage. Join Nick now on a stroll through the countryside, from his boat on a quiet part of the Thames up to some sheltered hilltop woods crossing two very differently managed estates, and at least one forbidden fence line. As he explains, success for The Right to Roam campaign would really look like.

The Right to Roam Campaign was launched when The Book of Trespass came out, because we basically realised, actually, it's the publishers its Bloomsbury, that we'll be getting all of these column inches in the newspapers or getting all the podcasts, and the radio interviews and the telly and whatnot. And actually, what an incredible amount of momentum we could have if we were to launch a campaign on that as well. And that momentum has just worked. Basically, it's just, it's launched the campaign, we're now you know, two years down the line in Westminster, and it's looking very likely that we're going to succeed as well, which has just taken everyone by surprise, really.

What we're walking on now is the whole estate it's 900 acres. So, there's lots of different, you know, there's forestry that goes on. Up on the hill. There's this organic farm, there's a cattle farmer called James Norman, that is a tenant on quite a lot of the land. And then there's enough space for other people in the community. To come up with our own ideas, you know, Kristen's got an allotment here, basically, growing loads of rosemary and basil and that kind of thing. She's got this massive distillery, that she turns it into, you know, sort of essential oils, or that kind of thing. It's just an example of the kind of thing that people can do. If you have, you know, the privilege of living on the estate, is that you have a space. And as long as you don't damage the environment, as long as you're actually contributing in some way to the community and the environment is part of that, idea of community. Then by and large, you're allowed to do it.

Well, I guess success for our campaign means a full right to roam. So, the right to be able to swim or kayak or paddleboard in your rivers, the right to wild camp, responsibly in places that are far away from, you know, people's dwellings, the right to be able to walk or to climb in England's beautiful open spaces. And you know, just following on from the Scottish Right to Roam, what we'd be looking for, is what they have, which is the Scottish Outdoor Access Code, which actually deals with all of the, kind of the, issues that you might face if you know with access to, to farmland or to forestry, up there, it's just worked really, really well people. You know, it's not just, it's not just that people are able to access the outdoors. Our point is that how can people be asked to care that the Linnet is down 59% since the 70s, or that the nightingale is on teetering on extinction, if you've grown up without ever having heard the nightingale. So, what we want, what we need is for people to be able to access and connect to nature, to really start to care about it on a visceral level. And so that's what success would look like, that's it would actually get us to a stage where we could then start campaigning for its improvement. You know, whether that means rewilding, or what we're more kind of keen on, is that idea of re-commoning, you can rewild an area of landscape but by and large, how that translates in England at the moment is further exclusion of the public. But if you want that to be sustainable, you really need the community, the local community, to be involved in that rewilding. And for that, obviously, they need access, they need a certain degree of autonomy to be able to connect in their own way to the nature around us.

We are walking down an old muddy path on the top of the valley, surrounded by long, very tall beech trees that haven't got the age to kind of widen out yet, or at least they've just shot upwards for the light. And we're just walking along this path. And then we'll go out to where the woodland ends and the valley kind of opens up. And we can kind of see the other estates from there. You can hear all the birdsong here, very loud. And when spring gets a bit warmer, you know, it's a problem for the sound people because they're the insects are so loud round here, you go on to this other estate, has been devastated by monoculture, industrial agriculture, you can literally hear the difference. Just in the noise, you know, there's nothing there. It's silent. Okay, let's take that path...

This thing here, this is the fence they keep erecting on this wide open hill, this is a right of way that goes down to like an ancient Anglo Saxon path that takes you all the way to Reading pretty much, which is legally protected. So, you're not allowed to cut him on that. But then the right of way comes all the way up the hill. But then this vast expanse in the valley, this other hill, where you can see all the red kites playing is officially private land. So, they put up this fence. And every year, unnamed locals come along, and literally, you can see, tear up the posts, and put it all down. You've just got all of this barbed wire, just in this kind of World War One tangle, that people, you can see the path that people have made with their feet over centuries, going there. And it to me, it's a really good example of how local people will actually just put their foot down and go 'nah, not this one'.

Well, we are using lots, or just recently, we started to use lots of myth and folklore in our campaigns, and when there's not mythological creatures, we've kind of invented them, you know, there was the, the estate we're just about to go onto. They tried to evict seven of our friends, a family of seven. Because they wanted to tart up the house, you know, just the standard kind of thing and then rent it to richer people. So, we invented a Silt Witch called 'Esme Boggart' and just basically told them that we were refusing, you know, you have no right to tear our community apart in that way, these people happen to be kind of central nodes of the kind of local art scene, you know, and they're very much beloved of all of us around here. And we were like, you live miles away in your other mansion. You have a legal right to evict these people with three months' notice, but you don't have the moral right. We say, "You know, we live here. You don't even live here you live ten miles away. You don't know what these people mean to us". So, by order of Esme Boggart go away, you know, and the weirdest thing of all, it worked, it kind of, to invoke these kind of old or new with Esme Boggart, but you know, it was sort of still based on old mythology. What we're really talking about is a kind of code of conduct and an understanding, with the nonhuman environment, with the communities that kind of creates these stories that are about the, the feeling the experience, experiential feeling of being in land or working with it. There's an eeriness to a full moon over a lake. So, a story or an idea or personification, kind of arises in the human mind, kind of the wildest thing we've got, even today is our imagination. And I tend to see the imagination as the link between our wilder selves. And this kind of slightly more, boxed up self that we've been handed as our personality.

Yes, so we started off on the boat down by the River Thames, kind of splashed our way across the floodplain, came up through the woods of the Hardwick Estate, and then came out on to another estate at the top of the valley where we can see the ribbon of the river, going from miles actually. And then just came, climbed a fence and came and sat in a lovely little copse of hawthorne, and ash and oak. And that's where we are now. The greatest trick that they've pulled is persuading everyone, instead of common ownership, that what you should do is work harder and get your own bit of it. That makes sense. And actually, people that do have a back garden, the thing that we get all the time is, well, you wouldn't want me coming over your back garden, you know, and camping in your back garden. And it's like if I own 6000 acres, I wouldn't even know about it. Because I'm not on 6000 acres, it's a different thing. Everyone has the right to privacy, everyone has the right to security. But they've co-opted that really essential human fear almost, of like someone kind of thick, just appearing in my backyard. And they've extrapolated that over, say two and a half thousand acres here. Like we're sat here we're not threatening anyone, and I have no intention. But if someone, if a gamekeeper saw us, he, because it would be a he, would feel that was a threat to his job, and to his personhood. If he didn't come over and aggressively shout at us and I still haven't stayed for the police. I've always gotten like 'yeah, all right, you know, we're going' -- but that's definitely this summer's job. Think we're gonna go on, me and my girlfriend's gonna go on, and set up camp on someone's land. And not leave and, and just see. But really what we want to do is bring landowners with us and show landowners how actually a closer connection with, between local communities and their land, will actually not just engender more respect for the environment, but more respect for the work that that landowners do. So, I think lockdown, contributed a lot to people both realising how much they loved, and needed nature, but also just going on the same path for you know, three lockdowns, looking over into the private forest and thinking well like why the hell isn't there a bit more variety here? Why can't we go there, that really contributed to the kind of mass picking up of our campaign.

For me to be able to, basically do this activism, I've had to monetize it in a way to be a writer first and then do the activism. But the problem with the book, is that people are satisfied that the book has lots of nice adjectives in it. You know, really like 'yeah, you put meant a lot to me kind of thing' and then you put it on the shelf and read another one. What it actually takes to get people out there to change something that is so inherently needs to be changed, can be quite frustrating. Sometimes. We're actually going to trial QR codes on this estate. And so, rather than a sign that says, or the sign that you guys sort of, you know, access only with permission or no trespassing, there are going to be little QR codes that you can scan on your phone, and it will tell you, James Norman, manages these flood plains at the moment especially lapwings, are nesting here, so rather than even putting your dogs on leads, we'd rather you didn't even come into these fields between say March and June, because there's an endangered species that is tentatively holding on, on this landscape. And we would rather that they, that they thrived on this landscape, than knew how to walk in this landscape. So, all of these things are possible. It's just, there's a status quo that doesn't want to accept that, because fundamentally, there will be a loss of power. And that power is a sort of Gollum, it's just like 'mine'. And it doesn't have to be just yours, it can still be yours, but you know, it could be ours.

Hopefully, that got you a little bit up in arms. But before you head off the storm parliament, check out @RighttoRoam on Instagram or go to righttoroam.org.uk to see how you can, more effectively support the campaign. Next time out, we're turning our focus from the whole of England, to some tiny pieces of Scotland, walking with interior designer Banjo Beal as he talks about designing in remote locations, finding a home in the Hebrides, and dragging oversized furniture to a lighthouse. If you haven't already, give us a follow on your podcast app. Tell a friend about the podcast, and check out at @Canopy&Stars on Instagram to see footage and photos from our days out recording.

A Life More Wild is an 18Sixty production, brought to you by Canopy & Stars. The producers for this episode were Gareth Evans and Eliza Lomas. Our theme music is by Billie Marten.