A life More Wild – Series 4, Episode 11

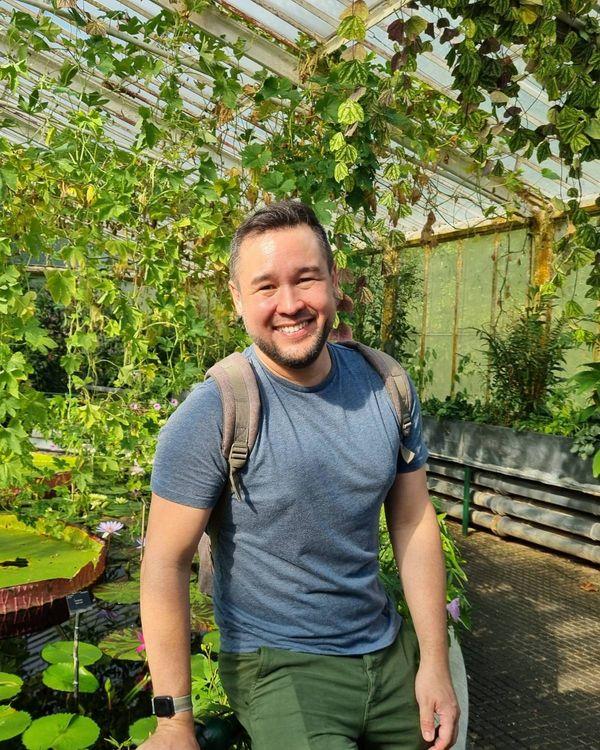

James Wong

James Wong on the full flat, ruined movies and inspiring insight that a love of plants has brought him

Join ethnobotanist James Wong for a tour of Kew gardens, to discover old-spice scented geraniums, Hollywood’s botanical errors and the biomimicry that shaped a London landmark.

The first time I came to Kew Gardens, I'd read about it. I'd heard about it, but I'd never been here before. I grew up on the other side of the world in Singapore, and I, we came to visit my grandma in the UK, and my mum took me when I was eight. And I remember walking into one of the glass houses and just going, Mum, is this what heaven looks like? And I kind of decided then and there that I had to, kind of be in and around this space. And it's, yeah, really nice that, like, 40 years, almost, later, it's still doing it. I'm here like three times a week.

So, we're starting into the area that I really should know the name of, but I don't. It's a Himalayan woodland-y area right in the centre of Kew, and it's this one part out of the hustle and bustle of our, everyone else has come and taking selfies. No one ever seems to come here. It's like a secret Oasis right in the centre.

I'm really surprised about the number of people that I know, even that live in London, but have never been to Kew, and I think it's because people might think of Botanic Gardens, like a public park, like it's a pretty place where you can walk the dog and look at some flowers. You can't actually walk your dog here, and that's because it's so much more than an aesthetic place. It's a place about plant conservation and cutting-edge plant research. There's one, like people often talk about the UK being a world leader in things. In reality, one of the few things that we're world leaders on, still, in the 21st century is botany and horticulture, and the epicentre of all of that is right here.

My specific training is as an ethnobotanist, and that's essentially a plant scientist that specifically looks at human plant use. There's lots of specialisms within botany, but what I find is fascinating, is that, that kind of when plants come up against humans, and humans decide they won't have a use for them. So whether that's food or whether that's medicine, or whether that's textiles, perfumes, timber, you know all the ways in which we use plants, and fundamentally, almost every aspect, of not just our basic biology, the fact that you know we have our eyes are on the front of our head, to give us good 3D vision, the fact that you know we have an appendix, our basic biology has dictated about billions of years of co-evolution with plants, as is almost every aspect of our psychology and our culture. We might not be able to see that today, but almost every aspect of how we organize society is based along agricultural lines, and that's all about growing plants.

Well, I think one of the reasons that definitely helped spur my interest in plants was growing up in Southeast Asia, and that's for two reasons. Firstly, I think you can only be interested in things you come into contact with, and just because of the climate, you come into contact with plants a lot more. So you can, you know, you can sow tomatoes any day of the year. I used to get these British gardening books, they'd say you have a six week window which you could sow tomatoes. And it's just so liberating to be able to grow anything any time of year, and also being in a cultural context where people still use plants. Plants aren't a quaint hobby for middle class people. They are, they're not outdoors kind of soft furnishings. They are solutions to everyday problems. So if you've got a headache, head out into the garden. If you're trying to figure out what to have for lunch today, head out into the garden.

This section is an area called the order beds. It's recently, I say recently. It's probably about ten years ago now it changed its format, but recently, compared to how long I've been coming here, and it's just a really amazing place to see a ridiculous diversity of plants in a tiny spot. Kew Gardens, according to which measure you're going to pick, could, is one of the most biodiverse spots on the planet, just because of all the amazing species you've got crammed into one tiny patch of West London.

We're walking past the kitchen garden now, and it's, we were so lucky to have such a beautiful day way into September, golden sunshine everywhere, beautiful breeze, and we're about to go to a really historic part of the garden, which is when people first started coming from places like the Alpine regions of the world and finding weird and wonderful plants that could only grow on mountaintops. They tried to create an artificial mountaintop here at Kew that caters for the specific environments those plants really need to survive. So, it's a really special place.

I think one of the big downsides to being a botanist is that, I think it becomes all consuming. At least it's all consuming for me. So you're you're, sort of never working because you love your job so much, but you're also always working. And you know that may even extend into when you're in the cinema with your mates, infuriating them by picking out all the botanical holes. So, I mean, almost every aspect of Hollywood gets plants wrong, and, like, really, resoundingly wrong. So, you'll be watching something like Indiana Jones and Kingdom of the Crystal Skull. I think they're meant to be in Peru, and they're driving through an environment, and there's, it's meant to be the Amazon rainforest, and then every twist and turn they go to there's a, an artichoke. It's always the same artichoke plant, cut and pasted out stuck. And they're like, this Jeep runs over the same artichoke plant in like 15 locations. It with the exact same number of fruit on it, like 100 times. Or you'll watch Jurassic Park as I did when I was 13 years old. It first came out and blew my mind. And I wanted to become a botanist because of Dr Ellie Sattler, who could, you know, administer antibiotics to a triceratops, or could instantly look at extinct plants and say whether they're toxic or not. We actually can't even tell today whether certain plants are toxic or not, because the only way to know whether something's toxic is to run a clinical trial and intentionally poison people with them. So, for very good reasons, we don't do very many of those trials. So establishing toxicity is notoriously hard, let alone from a plant you've never seen before that you only know from the fossil record.

One of the most exciting things about Kew is how it's managed to pack together so much of the flora from all over the world in one space. And I'm not just talking about glass houses, which can mimic almost any environment. It's how that's done outside. And you know, within a five-minute walk, you can be from a Mediterranean environment right to an Alpine mountain top and then into an American prairie. And it's a way to visit the world just by looking at the miracle of the plants around you.

The first thing I ever really did in media when I stopped actually working at Kew Gardens, was a BBC show called Grow Your Own Drugs, which is very long time ago now, and I thought it was really important for people to be able to engage with plants in a much more meaningful way than just finding them beautiful, which is the standard way that we talk about plants in the UK as just decorative objects, but actually useful and functional ones. You know, up to 50% of the medicinal plants, or the conventional medicines that you might get on the NHS, or you might get in boots, originally come from natural sources, and there's lots of ways in which you can incorporate them really effectively in your life, for all sorts of complaints. And I think what that does is it gives people some autonomy over their healthcare, and it also helps them to see the natural world for what it is, which is an incredible source of biologically active compounds that can improve people's lives. I wonder, in today's world, whether I'd make that show, because I think that in a world where anti-Vax and anti-trust in science and medicine is on the rise. Whether there is a potential for people to misunderstand the nuance there. There's a big difference between saying, you know, you can make mint tea, and there's some really good evidence that that can help reduce indigestion or the symptoms of indigestion, and saying, don't take your heart meds, because some mint tea will fix that. And I think today I'll probably be a little bit wary about the nuance, or the ability for people to misunderstand the nuance in that message.

We're about to step into one of my favourite areas of Kew. And it's not just because it's indoors and protected against all weathers. It's also spectacularly beautiful. It's the Princess of Wales house laid out in the 80s, I think very late 70s, 80s, and it has a little bit, this is very dated reference, but anyone who'd seen Lost the early noughties series, feels a little bit like you got lost in the bunker from Lost, so mon your monolithic concrete modernist architecture and just crazy wild plants and you whatever you're feeling like, whatever's going on in the outside world, nothing bad could happen in this house. So, at the middle of winter, you go inside and all your problems evaporate.

Feel you need to hush. It's like going into a cathedral. Maybe I'm taking plants too seriously, but there's definitely a library vibe. I'm going to skip you through the fern area. You can hear the mist that's going off, into the main tropical area where there is a plant that transforms modern architecture. It's visually stunning, and it's around just for another month or so in season here at Kew spectacular.

Okay, let's have a wonder. You can actually feel the temperature go up as you go into this room, almost a wall of humidity, and that's because of the huge pond that's right in the centre. And the jewel in the centre of that pond is a giant water lily, Victoria Amazonica. Its pads are so big that the textbooks say a six-year-old could stand on them, or a baby could stand on them. I know that the horticulturist that used to work here is at least five foot eight, something like that, probably more, sorry Alberto. And he managed to stand on one of these without ripping it. They can hold an adult male's weight, and they're so enormous. In Victorian times, when this plant was first introduced, there was a kind of a mad dash amongst the British aristocracy to see who could get it to be the first to flower. And the big problem they had was its leaves are so enormous and so fast growing. And it was a newly introduced plant that they kept on having to build bigger glass houses, because they would just grow too quick for the size of the glass house. And eventually it became impossible to hold up a glass roof without loads of pillars that were wide enough for the plant. And astonishingly, the engineering solution that allowed them to be able to create a huge glass expanse without pillars was the underside of the leaf. If you flip over one of these enormous green leaves that can be, you know, almost a double bed size. When they get to their biggest, there's a structure of veins and arches that reinforce themselves. And it was inspired by that structure that they first created, The Crystal Palace in London. And essentially, almost every large building you see today without pillars started with The Crystal Palace, and that started with the race to grow a giant water lily and the structure of the leaves underneath.

I think that's the reason why I love tropical plants, because they're all so massive and so fast growing, and it makes you feel small, and makes you feel small in every way, it makes humanity feel small in the context of things. And I feel almost like in a children's book, this kind of Jurassic, enormous sized, primeval world. And I think the Victorians really thought that about the natural world, and they had a sense of excitement and pioneering, and a sense of discovery about the natural world.

So I’m going to take you through to the more arid environments, which, on a day like today, a little bit cooler, let's have a wander. A massive drop in temperature, and we stepped into an area that used to be The Canary Islands, but is now Madagascar. That's the wonderful thing that plants can do for you with a whole range of plants, including, actually quite a common bedding plant that you see outside in the UK all the time, the Madagascar Periwinkle, beautiful pink or white flowers. It's used in hanging baskets, and it's also used to treat certain types of cancer. I think that because it's so pretty, as you're having your pine and seeing it in a window box, you probably never make the connection that it also has this incredible alternative use. And the same people who might be seeing that plant every day, might think that plants don't have a role in modern medicine anymore.

Plants have been fighting to survive for millions of years, as have we. But you know, we can either fight back or run away or hide or do all kinds of things because we're mobile. Plants are not mobile, so they've had to evolve a completely different strategy, and that's creating chemical weapons to defend themselves, whether that's a sunscreen to protect themselves from UV light, whether that's cell toxic like this produces, it's just that we're using their toxic compounds to kill cancer cells, whether it's antiviral or antibacterial or anti-inflammatory, they've had to come up with these incredible compounds. So, if you're if you're bioprospecting, if you're trying to find a biologically active compound. That actually does have some effect on the human body. You can create it in a lab, and it's a very efficient way of doing things. But the natural world is a really great place to start, because a random lottery has been working for billions of years to come up with these compounds, and sometimes they're already there.

This is one of my favourite spots, today. And also, you know, decades ago, when I was a student here. Right at one of the entrances of the house, there's a South African area, and in it there's lots of pelargoniums, or what you know, people would more commonly probably refer to as geraniums. And they look like the kind of thing that you would have in a hanging basket, and many of them are, but this whole section has a group of ones that have scented leaves, and they have an amazing ability to mimic other plants. So one might smell of peppermint, the other one of lemon, the other one of cinnamon, the other one of pine. And there's been breeding work to mix and match their scents. So one of them is called Old Spice, and it does smell exactly as all my uncles smelt in the 80s. There's one called Cola Bottles, and it's exactly it's not cola the drink. It's 100% the rip off gummy candy scent. And by mixing and matching and through breeding, creating all of these different compounds, and then crossing them, they've come up with almost every scent imaginable. And it is just kind of a weirdly fascinating and relaxing, scratch and sniff exercise. There's one that's just like blackcurrants. In fact, most natural rose flavouring, or rose scent that doesn't come from roses, really comes from rose geranium, because it produces way more of this rosy scented compounds for a much cheaper price than actual roses.

It's amazing how smell triggers memory. I'm instantly about seven years old, at my neighbour's house in Singapore, who used to make a drink called Bandung, which is Rose syrup in milk, artificially flavoured, fluorescent pink rose syrup. And it's exactly that. It's kind of bubblegum Barbie pink, really sickeningly sweet Turkish delight, in a wonderful way.

And so, we're just stepping out the glass house into the autumnal sunshine. You can see, you know, it's permanent somewhere in there, but the orange is just about to begin to blush on the trees outside here.

I don't have a garden at all, and people find that surprising. I think if you're born in my generation, it's really not that surprising. I would have to sell quite a few million copies of books before I could afford anything more than a flat in central London. And I think that traditionally, people do think about that as a huge barrier to growing plants, myself included, because I was always brought up with the idea of what the proper garden should be like, and it was very much until very recently, a one size fits all idea. But I think that having spent a lot of time trying to grow plants against the odds, trying to grow them indoors, has taught me a lot of things, and one of them is that indoor horticulture isn't, not proper horticulture. It's not some kind of inferior or second-class horticulture, as it's often talked about in the industry. It's actually the best form of horticulture in many ways, because, just for starters, not everyone has a garden so, but most people have a place to live. Most people have a windowsill, so it's automatically the most democratic one. Everything we know about the benefits of green space for mental and physical health is about proximity and the amount of time you spend with them. So, even if I had an outdoor space, I would still be, and I'm a massive outdoorsy person, I would still be spending more time in close proximity with my house plants than any of my other plants. And the fact that you know it can be February, it can be pouring down with rain, it can be 10.30 at night, I can still garden. Pretty much no gardener is still going to be gardening under those conditions.

One of the first questions I always get when people find out I'm a botanist. You know, if it's a cab driver or just random stranger down the pub is, you know, why are you interested in plants? What made you first interested in them? And I think that's a really surprising and quite revealing question about how people think about plants, because no one's ever asked my football-mad Brother, have you ever been interested in like, what was the trigger? Did you have a really influential teacher? Did the love of football run in your family? They're the questions I get about plants. But plants are the most fundamental, fascinating aspect of our universe. They're the solution to almost every problem that faces humanity, from climate change to species lost to food security. I kind of think it's weird that people aren't interested in plants. It's kind of the other way around to me, but I've been fascinated with them since I can remember. I can't remember a point of my life where I didn't find plants fascinating.

Keep track of all James’s work on his Instagram and follow us on ours to see behind the scenes footage from recordings and a few extra questions we asked each guest.

A Life More Wild is an 18Sixty production, brought to you by Canopy & Stars. Production by Clarissa Maycock. Our theme music is by Billie Marten.